Peras Technical Report #1

This technical report was written based on a now outdated version of the protocol.

The goal of this document is to provide a detailed analysis of the Peras protocol from an engineering point of view, based upon the work done by the Innovation team between November and April 2024. The design of the protocol itself is carried out by the Research team and is not the focus of this document as the paper is still actively being worked on.

Executive summary

This section lists a number of findings, conclusions, ideas, and known risks that we have garnered as part of the Peras innovation project.

Findings

Product-wise

We built evidence that the Peras protocol in its most recent incarnation can be implemented on top of Praos, in the existing ouroboros-consensus codebase, without compromising the core operations of the node (block creation, validation, and diffusion):

- Network Modelling has shown initial versions would add an unbearable overhead to block diffusion,

- Simulation and prototyping have allowed us to sketch implementation and better understand the interplay between Peras and Praos,

- Decoupling votes and certificates handling from blocks handling could pave the way to a smooth incremental building and deployment of Peras,

- While still not formally evaluated (see Remaining questions section) it seems the impact of vote and certificates diffusion on node operation will not be significant and the network will provide strong guarantees those messages can be delivered in a timely fashion.

We clarified the expected benefits of Peras over Praos expressed in terms of settlement failure probabilities: Outside cool-down period, with the proper set of parameters, Peras provides the same probability of settlement failure than Praos faster by a factor of roughly 1000, i.e. roughly 2 minutes instead of 36 hours.

Process-wise

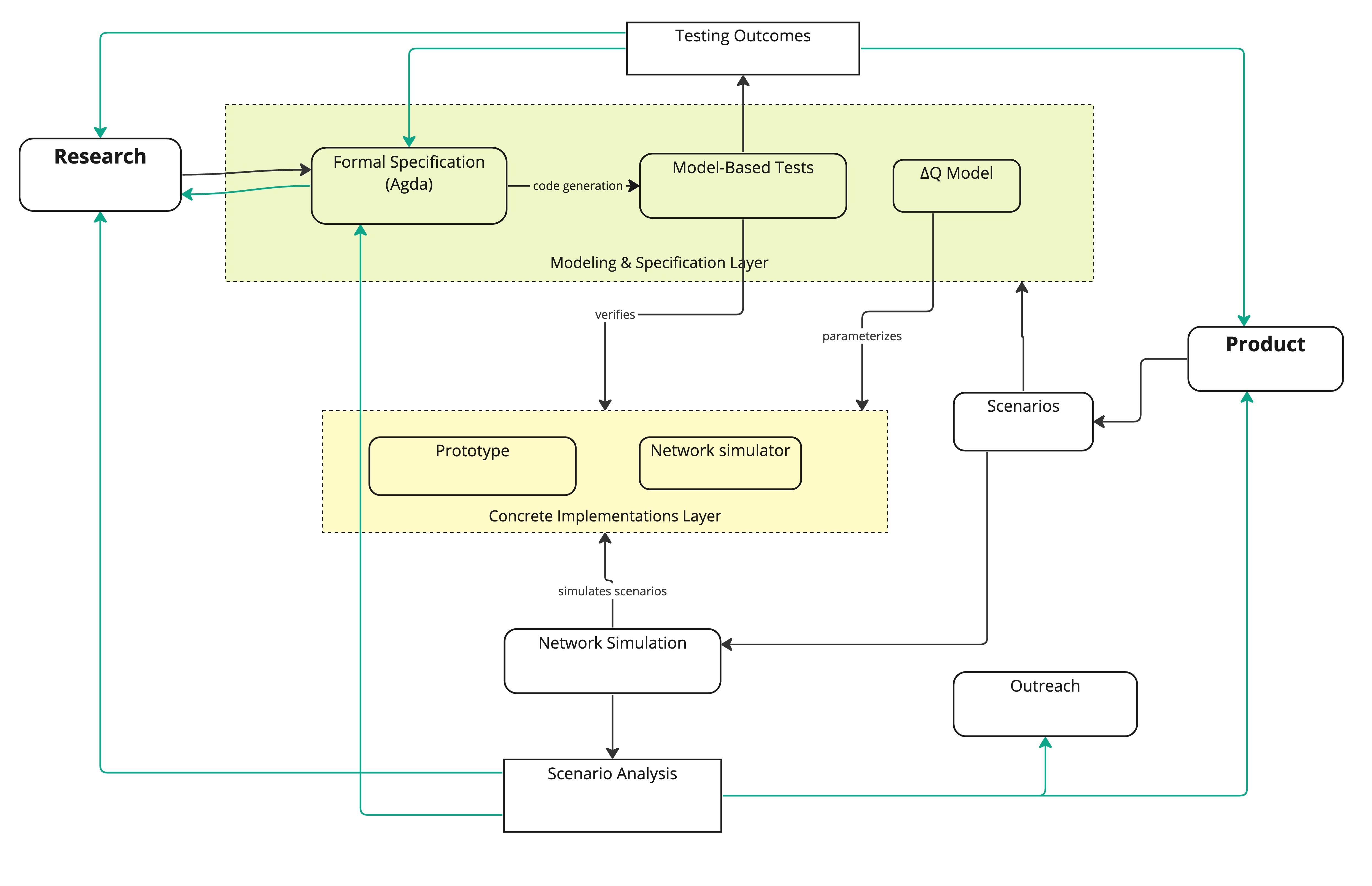

The following picture sketches the architecture of the project and the interaction between the various "domains" relevant to Innovation team. Black lines represent implemented direct relations, grey lines and boxes represent planned relations and tools, green lines represent expected feedback relations.

We confirmed the relevance of ΔQ modeling technique to provide insights on a protocol's performance profile, and how particular design decisions (even apparently minor ones) can impact this performance profile. We also gave feedback to the maintainers on the current state of the tool and libraries, and how to improve it in order to increase the reach of this technique.

We explored the use of formal modeling language Agda to specify the protocol and application of Proof-of-Stake-specific proof techniques to state and prove relevant properties of the protocol. We also started work on building a trail of evidence from research to implementation by:

- Experimenting with Quviq on the generation of quickcheck-dynamic test models from Agda models,

- Sketching a research-centric Domain Specific Language that could be used in research papers and as a foundation for formal modeling and engineering work.

While prototyping, we demonstrated the applicability of an Agda-centric chain of evidence even to "foreign" languages by testing with quickcheck-dynamic the same properties against Haskell and Rust prototypes, collaborating with the Creative engineering team on sketching a network simulator library in Rust.

Remaining questions

There remain a number of open questions that could be investigated in future work increments.

- Peras features, both benefits and shortcomings, need to be aligned with business cases and overall strategy for scaling Cardano. This implies more research is needed in two directions:

- From a product and user perspective, to evaluate the actual value that Peras delivers and the possible countermeasures to its drawbacks (e.g. the risk of cool-down could be covered by an options or insurance premium mechanism),

- From a technical perspective, to explore the parameters space and find the best combinations.

- There are a number of components about which we have some ideas but no concrete figures or design:

- Certificate structure and capabilities,

- Vote and certificate CPU requirements and their possible impact on the node,

- Optimal committee size,

- The protocol leaves room for a wide choice of options to design an implementation that should be considered and refined,

- There is a need for more theoretical research on ways to make cool-down less impactful.

Previous work

Peras workshop

The following sections recall the questions that were raised during the kick-off workshop in September 2023, points to the answers given, and details the SRL assessment along with a comparison with current estimated SRL.

Questions about Peras

For each of these questions we check whether or not it has been answered:

- How do you detect double voting? Is double voting possible? How can the voting state be bounded?

- each vote is signed individually and the signature is checked by the receiving node

- the voting state is bound by the committee size and the limited validity for each vote

- How are the voting committee members selected? What are the properties of the voting committee?

- Committee members are selected by a VRF-based sortition, its properties are exposed in the paper and overview

- Where should votes be included: block body, block header, or some other aggregate

- models and simulation show that votes need to be propagated and aggregated independently while not in cooldown period

- the "anchor" certificate used in cooldown period will need to be part of or attached to block bodies while its weight could be recorded as part of the corresponding block header

- Under what circumstance can a cool down be entered?

- The question of how much adversarial power is needed to trigger a cool-down period is still open

- How significant is the risk of suppressing votes to trigger a cool-down period?

- it is significant, as being able to trigger cool-downs often ruins the benefits of Peras

- Should vote contributions be incentivized?

- this question has not been explored in this report

- How much weight is added per round of voting?

- This is a parameter in the protocol whose exact value depends on business requirements

- How to expose the weight/settlement of a block to a consumer of chain data, such as a wallet?

- This has not been addressed yet, as most of the user-facing and business domain aspects of the protocol

- Can included votes be aggregated into an artifact to prove the existence of votes & the weight they provide?

- This is the role of certificates

Potential experiments for Peras

We refer the reader to the relevant section for each of those potential experiments to demonstrate (in)feasability of Peras:

- Network traffic simulation of vote messages

- This has been simulated but needs to be refined

- Protocol formalization & performance simulations of Peras

- Optimal look-back parameter (measured in number of slots) within a round

- Historic analytical study (- for reliability based on the number of 9s desired)

- Some parameters value are provided in the research paper and slides

- Chain growth simulations for the accumulation of vote data

- This has not been done as the protocol has evolved since the workshop

- Added chain catch-up time

- This is cool-down period length and is estimated in the slides

- Cost of diffusing votes and blocks that contain votes

- not estimated

- Need to refine: Details of VRF-based committee selection and its size

SRL

SRL (software readiness level) was initially assessed to be between 1 and 2, with the following definitions:

| Questions to resolve | Status |

|---|---|

| A concept formulated? | Done |

| Basic scientific principles underpinning the concept identified? | Done |

| Basic properties of algorithms, representations & concepts defined? | Done |

| Preliminary analytical studies confirm the basic concept? | |

| Application identified? | Done (Partner chains) |

| Preliminary design solution identified? | Partial |

| Preliminary system studies show the application to be feasible? | |

| Preliminary performance predictions made? | Done |

| Basic principles coded? | |

| Modeling & Simulation used to refine performance predictions further and confirm benefits? | |

| Benefits formulated? | |

| Research & development approach formulated? | Done |

| Preliminary definition of Laboratory tests and test environments established? | Preliminary |

| Experiments performed with synthetic data? | |

| Concept/application feasibility & benefits reported in paper |

We assess the current SRL to be between 3 and 4, given the following SRL 3 definition:

| Questions to resolve | Status |

|---|---|

| Critical functions/components of the concept/application identified? | Done |

| Subsystem or component analytical predictions made? | Partial |

| Subsystem or component performance assessed by Modeling and Simulation? | Partial |

| Preliminary performance metrics established for key parameters? | Done |

| Laboratory tests and test environments established? | Done |

| Laboratory test support equipment and computing environment completed for component/proof-of-concept testing? | N/A |

| Component acquisition/coding completed? | No |

| Component verification and validation completed? | Partial |

| Analysis of test results completed establishing key performance metrics for components/ subsystems? | Done |

| Analytical verification of critical functions from proof-of-concept made? | Done |

| Analytical and experimental proof-of-concept documented? | Done |

Protocol specification

Overview

A presentation of the motivation and principles of the protocol is available in these slides. We summarize the main points here but refer the interested reader to the slides for details.

- Peras adds a Voting layer on top of Praos, Cardano's Nakamoto-style consensus protocol.

- In every voting round, stakeholders (SPOs) get selected to be part of the voting committee through a stake-based sortition mechanism (using their existing VRF keys) and vote for the newest block at least slots old, where is a parameter of the construction (e.g., = 120 slots).

- Votes are broadcast to other nodes through network diffusion.

- If a block gains more than a certain threshold of votes (from the same round), a so-called quorum (), it gets extra weight (where each block has a base weight of 1). Since nodes always select the heaviest chain (as opposed to the longest chain in Praos), these blocks with extra weight accelerate settlement of all blocks before them.

- A set of votes (from the same round) can be turned into a short certificate. Certificates are needed during the cool-down period (see below), but they can also be broadcast to nodes that are catching up.

- If a quorum is not reached in a round, the protocol enters a cool-down period, in order to heal from the “damage” that could result from adversarial strategies centered around withholding adversarial votes. During the cool-down, voting is suspended, and block producers include information required to coordinate the restart (the latest known certificate) in their blocks. The duration of the cool-down period is roughly equal to the number of slots equivalent to produce k + B blocks, where k is the settlement parameter of Praos.

Certificates

The exact construction of Peras certificates is still unknown but we already know the feature set it should provide:

- A Peras certificate must be reasonably "small" in order to fit within the limits of a single block without leading to increased transmission delay.

- The current block size on

mainnetis 90kB, with each transaction limited to 16kB. - In order to not clutter the chain and take up too much block estate, a certificate should ideally fit in a single transaction.

- The current block size on

- Certificates need to be produced locally by a single node from the aggregation of multiple votes reaching a quorum.

- Certificate forging should be reasonably fast but is not critical for block diffusion: A round spans multiple possible blocks so there is more time to produce and broadcast it.

- A certificate must be reasonably fast to verify as it is on the critical path of chain selection: When a node receives a new block and/or a new certificate, it needs to decide whether or not this changes its best chain according to the weight,

- The ALBA paper provides a construction through a mechanism called a Telescope which seems like a good candidate for Peras certificates.

Pseudo-code

We initially started working from researchers' pseudo-code which was detailed in various documents. In the Paris Workshop in April 2024, we tried to address a key issue of this pseudo-code: The fact it lives in an unstructured and informal document, is not machine-checkable, and is therefore poised to be quickly out of the sync with both the R&D work on the formal specification, the prototyping work, and the research work. This collective effort led to writing the exact same pseudo-code as a literate Agda document, the internal consistency of which can be checked by the Agda compiler, while providing a similar level of flexibility and readability than the original document.

This document is available in the Peras repository and is a first step towards better integration between research and engineering work streams.

Next steps include:

- Refining the pseudo-code's syntax to make it readable and maintainable by researchers and engineers alike,

- Understanding how this code relates with the actual Agda code,

- Adding some semantics.

It is envisioned that at some point this kind of code could become commonplace in the security researchers community in order to provide formally verifiable and machine-checkable specifications, based on the theoretical framework used by researchers (e.g. Universal Composition).

Settlement time

Practical Settlement Bounds for Longest-Chain Consensus (Gazi, Ren, and Russell, 2023) provides a formal treatment of the settlement guarantees for proof-of-stake (PoS) blockchains.

Settlement time can be defined as the time needed for a given transaction to be considered permanent by some honest party. On Cardano, the upper bound for settlement time is to produce subsequent blocks, where is the security parameter and is the active slot coefficient. On the current mainchain, this time is 36 hours. Note that even if in practice the settlement time is fixed, in theory this bound is always probabilistic. The security parameter is chosen in such a way that the probability of a transaction being reverted after blocks is lower than .

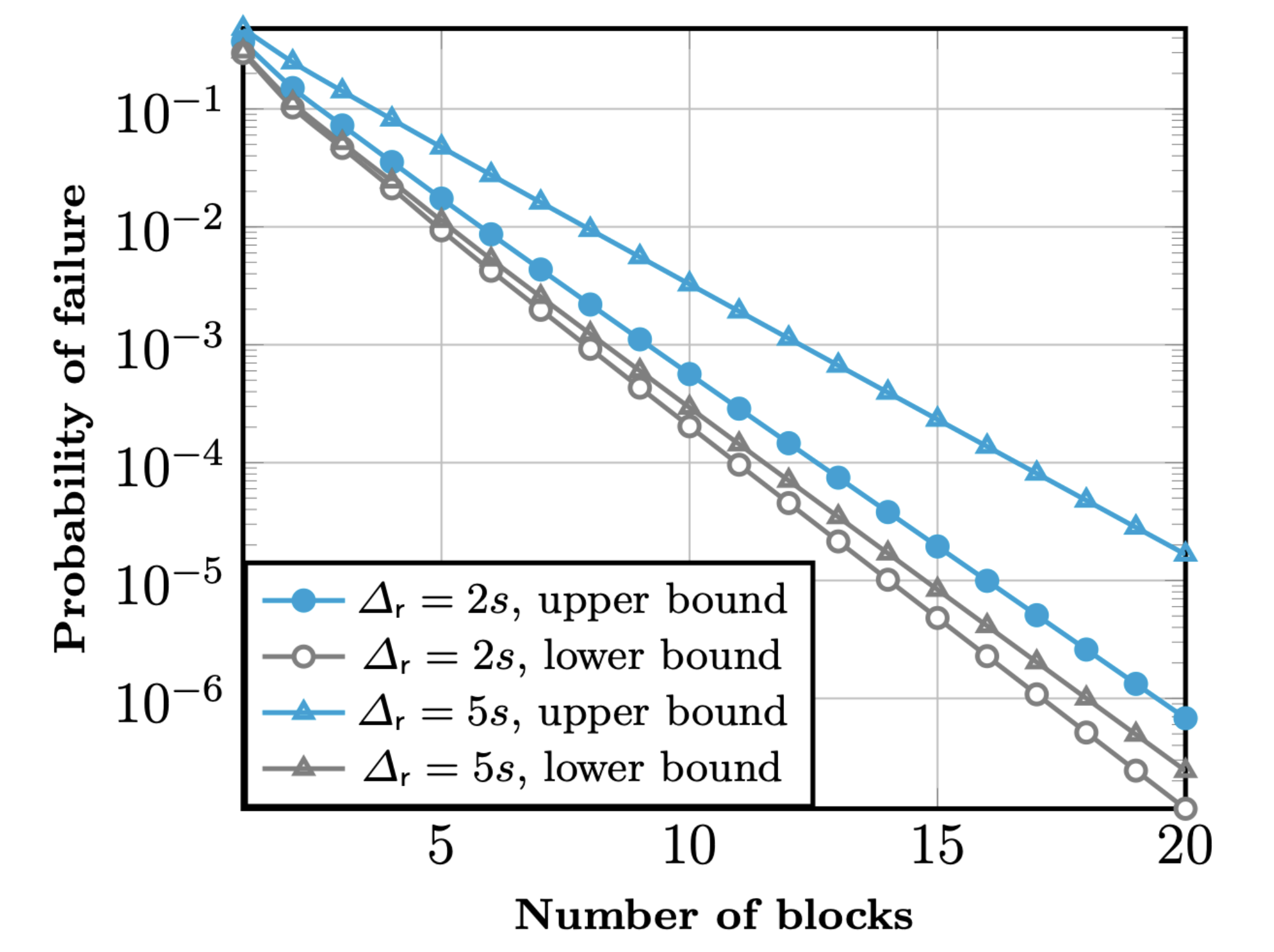

The following picture from the aforementioned paper shows block settlement failure probability given some block depth for Cardano PoS chain. Under the assumptions given there, the probability for a transaction to be rolled back after 20 blocks is 0.001% , and is exponentially decreasing with the block depth.

We also have anecdotal evidence from observations of the Cardano mainchain over the past few years that the settlement time is much shorter than the theoretical bound, as basically forks over 2 blocks length are exceedingly rare, and no fork over 3 blocks length has been observed on core nodes since the launch of Shelley.

There's however no evidence this situation will continue in the future, obviously, as it could very well be the case the network was never seriously under attack, hence we should take those numbers with caution.

Settlement bounds for Peras

Take the following analysis with a grain of salt as the researchers are still actively working on the protocol's security properties and numeric analysis.

While these numbers seem comforting and reasonably small to provide a very high degree of confidence after less than 10 minutes (a block is produced on average every 20s), it should be noted that they are based on non-existent to low adversarial power assumption (e.g. lower than 10% total stake), in other words they represent the best case scenario and say nothing about the potential impact of an adversary with significant resources and high motivation to either disrupt the network, e.g. as a form of denial of service to degrade the perceived value of Cardano, or more obviously to double spend. As the stakes increase and the network becomes more valuable, the probability of such an attack increases and our confidence in the settlement time should be adjusted accordingly.

In the optimistic case, Peras is expected to provide the level of settlement Praos provides after blocks but after only about a few rounds of voting. With the following parameters:

- Committee size ,

- Boost per certificate ,

- Quorum ,

- Round length slots.

we can expect a negligible () probability of settlement failure after 10 rounds or 100 slots, which is less than 2 minutes. In other words, Peras improves settlement upper bound over Praos by a factor of 1000, in the optimistic case, e.g. outside of a cool-down period.

However, triggering cool-down is cheap and does not require a large adversarial power as it is enough for an adversary to be able to create a relatively short fork that lasts slightly longer than the length of the voting window () to be able to force a split vote and a cool-down period.

Agda specification

The formal specification of the Peras protocol is implemented in Agda. It is a declarative specification, there are entities that are only defined by properties rather than by an explicit implementation. But still the specification is extractable to Haskell and allows to generate QuickCheck tests for checking an arbitrary implementation against the reference specification.

Domain model

The code here is substantially different from the pseudo-code mentioned before. These represent two different lines of work that ultimately should be reconciled.

The domain model is defined as Agda data types and implemented with Haskell code extraction in mind. The extractable domain model comprises entities like Block, Chain, Vote or Certificate. For example the Agda record type for Block

record Block where

field slotNumber : Slot

creatorId : PartyId

parentBlock : Hash Block

certificate : Maybe Certificate

leadershipProof : LeadershipProof

signature : Signature

bodyHash : Hash (List Tx)

is extracted to the Haskell data type:

data Block = Block

{ slotNumber :: Slot

, creatorId :: PartyId

, parentBlock :: Hash Block

, certificate :: Maybe Certificate

, leadershipProof :: LeadershipProof

, signature :: Signature

, bodyHash :: Hash [Tx]

}

deriving (Eq)

Cryptographic functions are not implemented in the specification. For example, for hash functions there is the record type Hashable

record Hashable (a : Set) : Set where

field hash : a → Hash a

that is extracted to a corresponding type class in Haskell:

class Hashable a where

hash :: a -> Hash a

For executing the reference specification, an instance of the different kind of hashes (for example for hashing blocks) needs to be provided.

Agda2hs

In order to generate "readable" Haskell code, we use agda2hs rather than relying on the standard Haskell generator code (MAlonzo) directly. It happens that agda2hs is not compatible with the Agda standard library and therefore we are using the custom Prelude provided by agda2hs that is also extractable to Haskell.

For extracting properties from Agda to Haskell we can use a similar type as the Equal type from the agda2hs examples. The constructor for Equal takes a pair of items and a proof that those are equal. When extracting to Haskell the proof gets erased. We can use this idea for extracting properties to be used with quick-check.

prop-genesis-in-slot0 : ∀ {c : Chain} → (v : ValidChain c) → slot (last c) ≡ 0

prop-genesis-in-slot0 = ...

propGenesisInSlot0 : ∀ (c : Chain) → (@0 v : ValidChain c) → Equal ℕ

propGenesisInSlot0 c v = MkEqual (slot (last c) , 0) (prop-genesis-in-slot0 v)

Small-step semantics

In order to describe the execution of the protocol, we are proposing a small-step semantics for Ouroboros Peras in Agda based on ideas from the small-step semantics for Ouroboros Praos as laid out in the PoS-NSB paper. The differences in the small-step semantics of the Ouroboros Praos part of the protocol are explained in the following sections.

Local state

The local state is the state of a single party, respectively a single node. It consists of a declarative blocktree, i.e. an abstract data structure representing possible chains specified by a set of properties. In addition to blocks, the blocktree for Ouroboros, Peras also includes votes and certificates and for this reason there are additional properties with respect to those entities.

The fields of the blocktree allow to:

- Extend the tree with blocks and votes,

- Get all blocks, votes and certificates,

- Get the best chain.

The property stating that the best chain is always a valid chain is such a property:

valid : ∀ (t : tT) (sl : Slot)

→ ValidChain (bestChain sl t)

The condition which chain is considered the best is given by the following property:

optimal : ∀ (c : Chain) (t : tT) (sl : Slot)

→ let b = bestChain sl t

in

ValidChain c

→ c ⊆ allBlocksUpTo sl t

→ weight c (certs t c) ≤ weight b (certs t b)

In words, this says that the best chain is valid (ValidChain is a predicate asserting that a chain is valid with respect to Ouroboros Praos) and the heaviest chain out of all valid chains is the best.

Global state

In order to describe progress with respect to the Ouroboros Peras protocol, a global state is introduced. The global state consists of the following entities:

- clock: Keeps track of the current slot of the system.

- state map: Map storing local state per party, i.e. the blocktrees of all the nodes.

- messages: All the messages that have been sent but not yet delivered.

- history: All the messages that have been sent.

- adversarial state: The adversarial state can be anything, with the type is passed to the specification as a parameter.

The differences compared to the model proposed in the PoS-NSB paper are:

- the execution order is not stored in the global state and therefore permutations of the messages as well as permutations of parties are not needed,

- the

Progressof the system as described in the PoS-NSB paper is not stored in the global state, as we define the global relation more granular

Instead of keeping track of the execution order of the parties in the global state, the global relation is defined with respect to parties. The list of parties is considered fixed from the beginning and passed to the specification as a parameter. Together with a party, we know as well the party's honesty (Honesty is a predicate for a party).

Instead of keeping track of progress globally we only need to assert that before the clock reaches the next slot, all the deliverable messages (i.e. messages where the delay is 0) in the global message buffer have been consumed.

Global relation

The protocol defines messages to be distributed between parties of the system. The specification currently implements the following message types:

- Block message: When a party is the slot leader a new block can be created and a message notifying the other parties about the block creation is broadcast. Note that, in case a cool-down phase according to the Ouroboros Peras protocol is detected, the block also includes a certificate that references a block of the party's preferred chain,

- Vote message: When a party creates a vote according to the protocol, this is wrapped into a message and delivered to the other parties.

The global relation expresses the evolution of the global state:

data _↝_ : Stateᵍ → Stateᵍ → Set where

Deliver : ∀ {M N p} {h : Honesty p} {m}

→ h ⊢ M [ m ]⇀ N

--------------

→ M ↝ N

CastVote : ∀ {M N p} {h : Honesty p}

→ h ⊢ M ⇉ N

---------

→ M ↝ N

CreateBlock : ∀ {M N p} {h : Honesty p}

→ h ⊢ M ↷ N

---------

→ M ↝ N

NextSlot : ∀ {M}

→ Delivered M

-----------

→ M ↝ tick M

The global relation consists of the following constructors:

- Deliver: A party consuming a message from the global message buffer is a global state transition. The party might be honest or adversarial, in the latter case a message will be delayed rather than consumed,

- Cast vote: A vote is created by a party and a corresponding message is put into the global message buffer for all parties respectively,

- Create block: If a party is a slot leader, a new block can be created and put into the global message buffer for the other parties. In case that a chain according to the Peras protocol enters a cool-down phase, the party adds a certificate to the block as well,

- Next slot: Allows to advance the global clock by one slot. Note that this is only possible, if all the messages for the current slot are consumed as expressed by the

Deliveredpredicate.

The reflexive transitive closure of the global relation describes what global states are reachable.

Proofs

The properties and proofs that we can state based upon the formal specification are in Properties.lagda.md.

A first property is knowledge-propagation, a lemma that states that knowledge about blocks is propagated between honest parties in the system. In detail the lemma expresses that for two honest parties the blocks in the blocktree of the first party will be a subset of the blocks of the second party after any number of state transitions into a state where all the messages have been delivered. Or in Agda:

knowledge-propagation : ∀ {N₁ N₂ : GlobalState}

→ {p₁ p₂ : PartyId}

→ {t₁ t₂ : A}

→ {honesty₁ : Honesty p₁}

→ {honesty₂ : Honesty p₂}

→ honesty₁ ≡ Honest {p₁}

→ honesty₂ ≡ Honest {p₂}

→ (p₁ , honesty₁) ∈ parties

→ (p₂ , honesty₂) ∈ parties

→ N₀ ↝⋆ N₁

→ N₁ ↝⋆ N₂

→ lookup (stateMap N₁) p₁ ≡ just ⟪ t₁ ⟫

→ lookup (stateMap N₂) p₂ ≡ just ⟪ t₂ ⟫

→ Delivered N₂

→ clock N₁ ≡ clock N₂

→ allBlocks blockTree t₁ ⊆ allBlocks blockTree t₂

Knowledge propagation is a pre-requisite for the chain growth property, it informally states that in each period, the best chain of any honest party will increase at least by a number that is proportional to the number of lucky slots in that period, where a lucky slot is any slot where an honest party is a slot leader.

Network performance analysis

We provide in this section the methodology and results of the analysis of the Peras protocol performance in the context of the Cardano network. This analysis is not complete as it only covers the impact of including certificates in block headers, which is not a property of the protocol anymore. More analysis is needed on the votes and certificates diffusion process following changes to the protocol in March 2024.

Certificates in block header

This section provides high-level analysis of the impact of Peras protocol on the existing Cardano network, using ΔQSD methodology. In order to provide a baseline to compare with, we first applied ΔQ to the existing Praos protocol reconstructing the results that lead to the current set of parameters defining the performance characteristics of Cardano, following section 4 of the aforementioned paper. We then used the same modeling technique taking into account the Peras protocol assuming inclusion of certificates in headers insofar as they impact the core outcome of the Cardano network, namely block diffusion time.

One of the sub-goals for Peras project is to collaborate with PNSol, the original inventor of ΔQ methodology, to improve the usability of the whole method and promote it as a standard tool for designing distributed systems.

Baseline - Praos ΔQ modeling

Model overview

Here is a graphical representation of the outcome diagram for the ΔQ model of Cardano network under Praos protocol:

This model is based on the following assumptions:

- Full block diffusion is separated in a number of steps: request and reply of the block header, then request and reply of the block body,

- Propagating a block across the network might require several "hops" as there is not a direct connection between every pair of nodes, with the distribution of paths length depending on the network topology,

- We have not considered the probability of loss in the current model.

The block and body sizes are assumed to be:

- Block header size is smaller than typical MTU of IP network (e.g. 1500 bytes) and therefore requires a single roundtrip of TCP messages for propagation,

- Block body size is about 64kB which implies propagation requires several TCP packets sending and therefore takes more time.

As the Cardano network uses TCP/IP for its transport, we should base the header size on the Maximum Segment Size, not the MTU. This size is 536 for IPv4 and 1220 for IPv6.

Average latency numbers are drawn from table 1 in the paper and depend on the (physical) distance between 2 connected nodes:

| Distance | 1 segment RTT (ms) | 64 kB RTT (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| Short | 12 | 24 |

| Medium | 69 | 143 |

| Long | 268 | 531 |

For each step in the diffusion of a block, we assume an equal () chance for each class of distance.

The actual maximum block body size at the time of this writing is 90kB, but for want of an actual delay value for this size, we chose the nearest increment available. We need to actually measure the real value for this block size and other significant increments.

We have chosen to define two models of ΔQ diffusion, one based on an average node degree of 10, and another one on 15. Table 2 gives us the following distribution of paths length:

| Length | Degree = 10 | Degree = 15 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.40% | 0.60% |

| 2 | 3.91% | 8.58% |

| 3 | 31.06% | 65.86% |

| 4 | 61.85% | 24.95% |

| 5 | 2.78% | 0 |

These numbers are reflected (somewhat inaccurately) in the above graph, representing the probabilities for the number of hops a block will have to go through before reaching another node.

The current target valency for cardano-node's connection is 20, and while there are a large number of stake pools in operation, there is some significant concentration of stake, which means the actual number of "core" nodes to consider would be smaller and the distribution of paths length closer to 1.

Modeling process

We have experimented with three different libraries for encoding this baseline model:

- Original ΔQ library built by Neil Davies, which uses randomized sampling to graph the Cumulative Distribution Function resulting from the ΔQ model,

- A library for algebraic representation of ΔQ models built to support the Algebraic Reasoning with Timeliness paper, which uses discretization of probability density functions to approximate CFDs resulting from the various ΔQ language combinators,

- Another recent library built by Peter Thompson to represent ΔQ probability distributions using piecewise polynomials, which should provide high-fidelity CDFs.

Library 2 was used to express the outcome diagram depicted above using so-called O language, but while we were able to encode the model itself, the resulting computation of CDFs for composite expressions resulting from convolution of atomic expressions turned out to be unusable, yielding CDFs with accumulated probability lower than 1 even though we did not model any loss. Library 3, although the most promising to provide accurate models, turned out to be unsatisfactory as we were not able to produce proper numerical representations of a CDF for more complex expressions.

Using code from library 1, we were able to write the following ΔQ expressions to represent our Cardano model:

oneMTU =

fromQTA @SimpleUniform

[(0, 0), (1 % 3, 0.012), (2 % 3, 0.069), (3 % 3, 0.268)]

blockBody64K =

fromQTA @SimpleUniform

[(0, 0), (1 % 3, 0.024), (2 % 3, 0.143), (3 % 3, 0.531)]

headerRequestReply = oneMTU ⊕ oneMTU -- request/reply

bodyRequestReply = oneMTU ⊕ blockBody64K -- request/reply

oneBlockDiffusion = headerRequestReply ⊕ bodyRequestReply

combine [(p, dq), (_, dq')] = (⇋) (toRational $ p / 100) dq dq'

combine ((p, dq) : rest) = (⇋) (toRational $ p / 100) dq (combine rest)

multihops = (`multiHop` oneBlockDiffusion) <$> [1 ..]

pathLengthsDistributionDegree15 =

[0.60, 8.58, 65.86, 24.95]

hopsProba15 = zip (scanl1 (+) pathLengthsDistributionDegree15 <> [0]) multihops

deltaq15 = combine hopsProba15

Then computing the empirical CDF over 5000 different random samples yield the following graph:

To calibrate our model, we have computed an empirical distribution of block adoption time1 observed on the mainnet over the course of 4 weeks (from 22nd February 2024 to 18th March 2024), as provided by https://api.clio.one/blocklog/timeline/. The raw data is provided as a file with 12 millions entries similar to:

9963861,117000029,57.128.141.149,192.168.1.1,570,0,60,30

9963861,117000029,57.128.141.149,192.168.1.1,540,0,60,40

9963861,117000029,158.101.97.195,150.136.84.82,320,0,10,50

9963861,117000029,185.185.82.168,158.220.80.17,610,0,50,50

9963861,117000029,74.122.122.114,10.10.100.12,450,0,10,50

9963861,117000029,69.156.16.141,69.156.16.141,420,0,10,50

9963861,117000029,165.227.139.87,10.114.0.2,620,10,0,70

9963861,117000029,192.99.4.52,144.217.78.44,460,0,10,100

9963861,117000029,49.12.89.235,135.125.188.228,550,0,20,50

9963861,117000029,168.119.9.11,3.217.90.52,450,150,10,50

...

Each entry provides:

- Block height,

- Slot number,

- Emitter and receiver's IP addresses,

- Time (in ms) to header announcement,

- then additional time to fetch header,

- time to download block,

- and finally time to adopt a block on the receiver.

Therefore the total time for block diffusion is the sum of the last 4 columns.

This data is gathered through a network of over 100 collaborating nodes that agreed to report various statistics to a central aggregator, so it is not exhaustive and could be biased. The following graph compares this observed CDF to various CDFs for different distances (in the graph sense, e.g. number of hops one need to go through from an emitting node to a recipient node) between nodes.

While this would require some more rigorous analysis to be asserted in a sound way, it seems there is a good correlation between empirical distribution and 1-hop distribution, which is comforting as it validates the relevance of the model.

Peras ΔQ model - blocks

Things to take into account for modeling Peras:

- Impact of the size of the certificate: If adding the certificate increases the size of the header beyond the MSS (or MTU?), this will impact header diffusion.

- We might need to just add a hash to the header (32 bytes) and then have the node request the certificate, which also increases (full) header diffusion time.

- Impact of validating the certificate: If it is not cheap (e.g. a few ms like a signature verification), this could also lead to an increase in block adoption time as a node receiving a header will have to add more time to validate it before sharing it with its peers.

- There might not be a certificate for each header, depending on the length of the rounds. Given round length R in slots and average block production length S, then frequency of headers with certificate is S/R.

- The model must take into account different paths for retrieving a header, one with a certificate and one without.

- Diffusion of votes and certificates does not seem to have other impacts on diffusion of blocks: e.g. just because we have more messages to handle and therefore we consume more bandwidth between nodes, this could lead to delays for block propagation, but it seems there is enough bandwidth (in steady state, perhaps not when syncing) to diffuse both votes, certificates, transactions, and blocks without one impacting the other.

The following diagram compares the ΔQ distribution of block diffusion (for 4 hops) under different assumptions:

- Standard block without a certificate,

- Block header points to a certificate.

Certificate validation is assumed to be a constant 50ms.

Obviously, adding a round-trip network exchange to retrieve the certificate for a given header degrades the "timeliness" of block diffusion. For the case of 2500 nodes with average degree 15, we get the following distributions, comparing blocks with and without certificates:

Depending on the value of , the round length, not all block headers will have a certificate and the ratio could actually be quite small, e.g. if then we would expect 1/3rd of the headers to have a certificate on average. While we tried to factor that ratio in the model, that is misleading because of the second order effect an additional certificate fetching could have on the whole system: More delay in the block diffusion process increases the likelihood of forks which have an adversarial impact on the whole system, and averaging this impact hides it.

In practice, cardano-node uses network-level pipelining to avoid having to request individually every block/header: e.g. when sending multiple blocks to a peer a node will not wait for its peer's request and will keep sending headers as long as not instructed to do otherwise.

This is not to be confused with consensus pipelining which streamlines block headers diffusion from upstream to downstream peers before waiting for full block body validation.

Conclusion

This analysis demonstrates that Peras certificates cannot be on the critical path of block headers diffusion lest we run the risk of increased delays in block diffusion and number of forks. Certificates either have to be small enough to not require an additional round-trip to transmit on top of the block header, or be part of the block body. Note that in the latter case the certificates should also be relatively small as there is limited space available in blocks.

Votes & certificates diffusion

Detailed analysis of votes and certificates diffusion is still ongoing and will be reported in a future document. Some preliminary discussions with PNSol allowed us to identify the following points to consider:

- The vote diffusion will very likely be unproblematic on "sunny days", so the modeling and thinking effort should be focused on "rainy days", e.g. what happens under heavy load, e.g. CPU load (also possibly network load?). These are the circumstances into which backpressure should be applied.

- Some key questions to answer to:

- How much computation do we do on each vote?

- How much computation do we do on each certificate?

- What kind of backpressure do we need to bake in?

- An interesting observation: We could build certificates to reduce the amount of data transferred, e.g. trading CPU time (building certificate) for space and network bandwidth consumption.

Impact on user experience

Model

We could want to model the outcomes of Peras in terms of user experience, e.g. how does Peras impact the user experience? From the point of view of the users, the thing that matters is the settlement time of their transactions: How long does it take for a transaction submitted to be settled, e.g. to have enough (how much?) guarantee that the transaction is definitely part of the chain?

From this point of view, the whole path from transaction submission to observing a (deep enough) block matters, which means we need to take into account in our modeling the propagation of the transaction through the mempools of various nodes in the network until it reaches a block producer. This also means we need to take into account the potential delays incurred in that journey that can occur because of mempool congestion in the system: When the mempool of a node is full, it will not pull more transactions from the peers that are connected to it.

The following diagram illustrates the "happy path" of a transaction until the block its part of gets adopted by the emitting node, in Praos.

sequenceDiagram

actor Alice

participant N1 as Node1

participant N2 as Node2

participant N3 as Node3

participant BP as Minter

N2 -->> +N1: Next tx

Alice ->> N1: Post tx

N1 ->> +N2: Tx id

N2 ->> +N1: Get tx

N1 ->> +N2: Send tx

BP -->> +N2: Next tx

N2 ->> +BP: Tx id

BP ->> +N2: Get tx

N2 ->> +BP: Send tx

BP ->> BP: Mint block

N2 ->> +BP: Next block

BP ->> N2: Block header

N2 ->> BP: Get block

BP ->> N2: Send block

N1 ->> +N2: Next block

N2 ->> N1: Block header

N1 ->> N2: Get block

N2 ->> N1: Send block

N1 -->> Alice: Tx in block

This question is discussed in much more detail in the report on timeliness and should be considered outside of the scope of Peras protocol itself.

Property-based testing with state-machine based QuickCheck

The quickcheck-dynamic Haskell package enables property-based testing of state machines. It is the primary testing framework used for testing the Peras implementations in Haskell and Rust. Eventually, the dynamic model instances used in quickcheck-dynamic will be generated directly from the Agda specification of Peras using agda2hs.

Testing that uses the standard (non-dynamic) quickcheck package is limited to the JSON serialization tests, such as golden and roundtrip tests and round-trip tests.

Praos properties

Praos NodeModel and NetworkModel test the state transitions related to slot leadership and forging blocks. They can be used with the Haskell node and network implemented in peras-iosim, or the Rust node and network implementation in peras-rust. This dual-language capability demonstrated the feasibility of providing dynamic QuickCheck models for language-agnostic testing. The properties tested are that the forging rate of a node matches the theoretical expectation to within statistical variations and that, sufficiently after genesis, the nodes in a network have a common chain-prefix.

Peras properties

A quickcheck-dynamic model was created for closer and cleaner linkage between code generated by agda2hs and Haskell and Rust simulations. The model has the following features:

The "idealized" votes, certificates, blocks, and chains of the QuickCheck model are separated from "realized" ones generated by agda2hs and used in the simulations. The idealized version ignores some details like signatures and proofs. It is possible to remove this separation between ideal and real if behaviors are fully deterministic (including the bytes of signatures and proofs). However, this prototype demonstrates the feasibility of having a slightly more abstract model of a node for use in Test.QuickCheck.StateModel.

The NodeModel has sufficient detail to faitfully represents Peras protocol. Ideally, this would be generated directly by agda2hs. This instance of StateModel uses the executable specification for state transitions and includes generators for actions, constrained by preconditions.

data NodeModel = NodeModel { ... }

instance StateModel NodeModel where

data Action NodeModel a where

Initialize :: Protocol -> PartyId {- i.e., the owner of the node -} -> Action NodeModel ()

ATick :: IsSlotLeader -> IsCommitteeMember -> Action NodeModel [MessageIdeal]

ANewChain :: ChainIdeal -> Action NodeModel [MessageIdeal]

ASomeCert :: CertIdeal -> Action NodeModel [MessageIdeal]

ASomeVote :: VoteIdeal -> Action NodeModel [MessageIdeal]

arbitraryAction = ...

precondition = ...

initialState = ...

nextState = ...

The executable specification for the node model is embodied in a typeclass PerasNode representing the abstract interface of nodes. An instance (Monad m, PerasNode n m) => RunModel NodeModel (RunMonad n m) executes actions on a PerasNode and checks postconditions. This also could be generated by agda2hs from the specification.

class Monad m => PerasNode a m where

newSlot :: IsSlotLeader -> IsCommitteeMember -> a -> m ([Message], a)

newChain :: Chain -> a -> m ([Message], a)

...

For demonstration purposes, an instance PerasNode ExampleNode implements a simple, intentionally buggy, node for exercising the dynamic logic tests. This could be a full Haskell or Rust implementation, an implementation generated via agda2hs from operational (executable) semantics in Agda, etc.

data ExampleNode = ExampleNode { ... }

instance PerasNode ExampleNode Gen where

...

The example property below simply runs a simulation using ExampleNode and checks the trace conforms to the executable specification.

propSimulate :: (Actions NodeModel -> Property) -> Property

propSimulate = forAllDL simulate

simulate :: DL NodeModel ()

simulate = action initialize >> anyActions_

-- | Act on the example node.

propOptimalModelExample :: Actions NodeModel -> Property

propOptimalModelExample actions = property . runPropExampleNode $ do

void $ runActions actions

assert True

-- | Test a property in the example node.

runPropExampleNode :: Testable a => PropertyM (RunMonad ExampleNode Gen) a -> Gen Property

runPropExampleNode p = do

Capture eval <- capture

flip evalStateT def . runMonad . eval $ monadic' p

Because the example node contains a couple of intentional bugs, one expects the test to fail. Shrinking reveals a parsimonious series of actions that exhibit one of the bugs.

spec :: Spec

spec = describe "Example node" . prop "Simulation respects model"

. expectFailure $ propSimulate propOptimalModelExample

$ cabal run test:peras-quickcheck-test -- --match "/Peras.OptimalModel/Example node/Simulation respects model/"

Peras.OptimalModel

Example node

Simulation respects model [✔]

+++ OK, failed as expected. Assertion failed (after 4 tests and 1 shrink):

do action $ Initialize (Peras {roundLength = 10, quorum = 3, boost = 0.25}) 0

action $ ANewChain [BlockIdeal {hash = "92dc9c1906312bb4", creator = 1, slot = 0, cert = Nothing, parent = ""}]

action $ ATick False True

pure ()

Finished in 0.0027 seconds

1 example, 0 failures

Relating test model to formal model

The team has been working with Quviq to provide assistance and expertise on tighter integration between the Agda specification and the quickcheck-dynamic model. This work resulted in the development of a prototype that demonstrates the feasibility of generating the quickcheck-dynamic model from the Agda specification, as described in Milestone 1 of the Statement of Work.

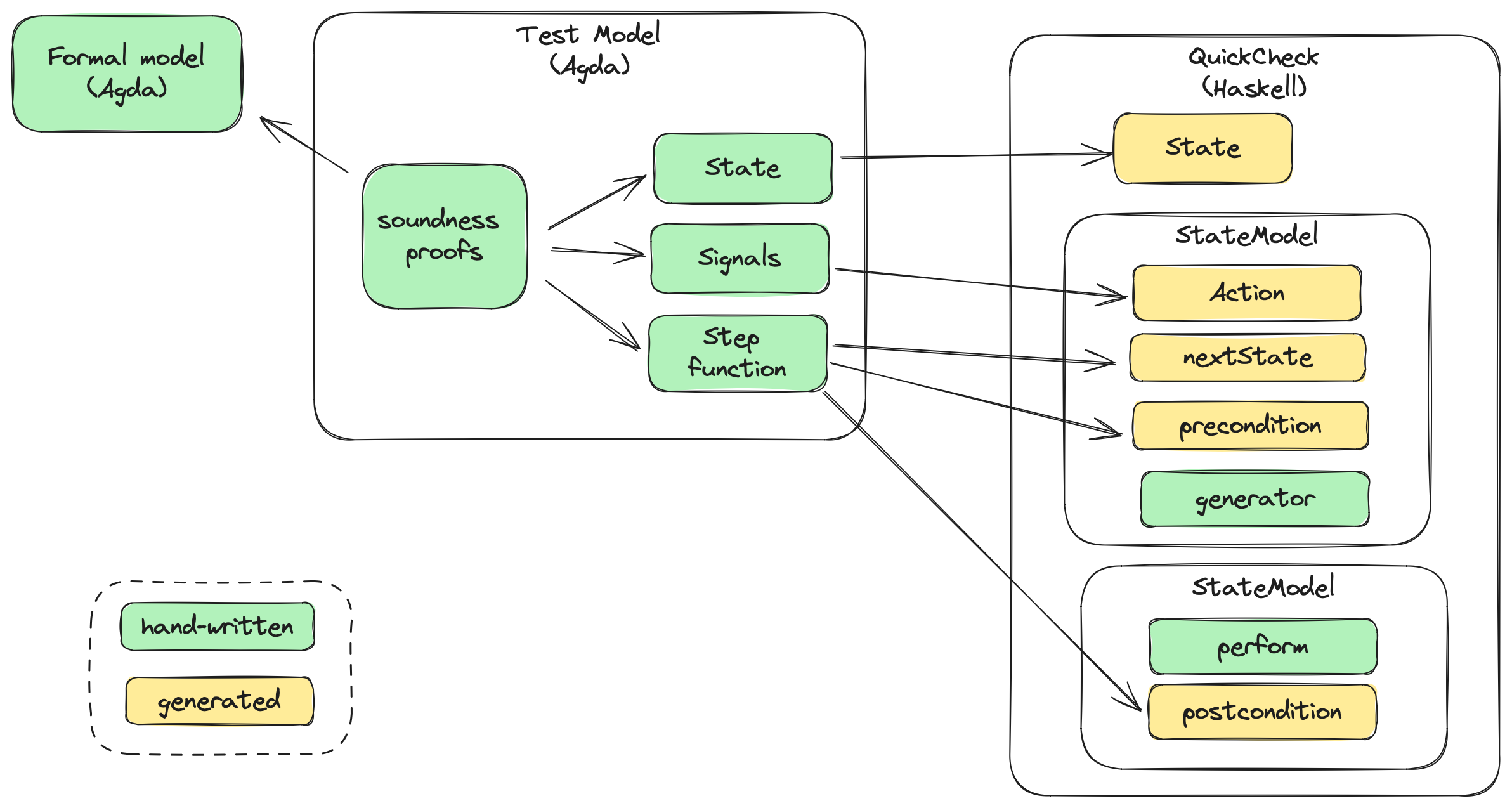

The following picture summarizes how the various parts of the testing framework for Peras are related:

The key points of this line of work are:

- While both written in Agda, we differentiate the Formal model from the Test model as they serve different purposes. More importantly, we acknowledge the fact there be more than one Test model for a given Formal model, depending on the level of abstraction and the properties we want to test,

- The Formal model is the actual specification of the protocol and is meant to write proofs related to the protocol (e.g the usual blockchain properties like chain growth, chain quality, etc. and the specific properties of Peras). Ideally, this model should be part of the research work and written in close collaboration with them,

- The Test model describes some relevant behavior of the system for the purpose of asserting a liveness or safety property, in the form of a state machine relating: A state data type, some signals sent to the SUT for testing purpose, and a step function describing possible transitions of the system,

- The Test model's soundness w.r.t the Formal model is proven through a soundness theorem that guarantees each sequence of transition in the Test model can be mapped to a valid sequence of transitions in the Formal model,

- Using

agda2hsHaskell code is generated from the Test model and integrated in a small hand-written wrapper complying with quickcheck-dynamic API, - Note the

performfunction is not generated because it's specific to the actual implementation of the System-Under-Test (SUT).

The provided models are very simple toy examples of some chain protocol as the purpose of this first step was to validate the approach and identify potential issues. In further steps, we need to:

- Work on a more complex and realistic Test model checking some core properties of the Peras protocol,

- Ensure the Formal model's semantics is amenable to testability and proving soundness of the Test model.

Simulations

In order to test the language-neutrality of the testing framework for Peras, we developed both Haskell-based and Rust-based simulations of the Peras and Praos protocols.

Haskell-based simulation

The initial phase of the first Peras PI's work on simulation revolves around discovery. This involves several key tasks, including prototyping and evaluating different simulation architectures, investigating simulation-based analysis workflows, assessing existing network simulation tools, establishing interface and serialization formats, eliciting requirements for both simulation and analysis purposes, and gaining a deeper understanding of Peras behaviors. The first prototype simulation, developed in Haskell, is closely intertwined with the Agda specification. This integration extends to the generation of types directly from Agda. Subsequent work will migrate a significant portion of the Peras implementation from Haskell to functions within the Agda specification, which will necessitate reconceptualizing and refining various components of the simulation.

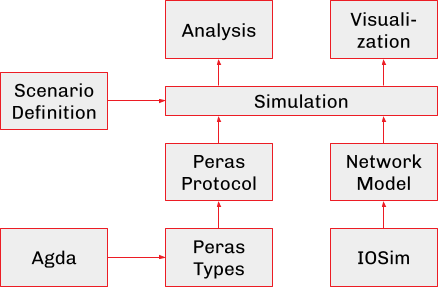

The Peras simulation employs language-agnostic components that collaborate seamlessly (see figure below). This includes node implementations in Haskell, with Rust implementations forthcoming. Additionally, the native-Haskell simulation utilizes the IOSim packages in a manner consistent with QuickCheck tests in peras-quickcheck, which also supports a Foreign Function Interface (FFI) connection to Netsim and peras-rust. The simulation setup also encompasses statistically designed experiments, the ability to inject rare events or adversarial behaviors, tools for generating networks and scenarios, as well as analysis and visualization tools to interpret the simulation results. A significant aspect of the workflow is geared towards analysis. This involves an observability approach to gathering metrics, utilization of language-independent file formats, visualization of network structures, and statistical analyses primarily conducted using R.

The IOSim-based Haskell simulator for Peras currently provides a provisional implementation of the Peras protocol's intricacies, including committee selection, voting rounds, and cool-down periods. Presently, the fidelity of the simulation to the Peras protocol is moderate, while the fidelity at the network layer remains low. Substantial refactoring and refinement efforts are deemed necessary moving forward to enhance the simulation's accuracy and effectiveness.

The simulation implements the February version of the Peras protocol, illustrated in the UML sequence diagrams below for node behavior, and the activity diagram for node state transitions. Nodes receive messages for entering a new slot or new voting round; they also receive new preferred chains or votes from their upstream peers via messages. When they vote, forge blocks, or adopt a new preferred chain, they notify their downstream peers via messages.

The detailed behavior of the February protocol differs somewhat from later versions such as the March protocol.

Design

The architecture, design, and implementation of the Haskell-based peras-iosim package evolved significantly during Peras's first PI, so here we just summarize the software approach that the series of prototypes has converged upon.

IOSim

The simulator initially relied heavily on io-sim and io-classes as it was inspired by similar work based on IOSim, like hydra-sim: Each node would be a separate actor, possibly running several threads. We then moved to a much more lightweight use of IOSim's capabilities.

First of all, IOSim's implementation is currently single-threaded with a centralized scheduler that handles the simulated threads. Thus, IOSim does not provide the speed advantages of a parallel simulator. However, it conveniently provides many of the commonly used MTL (monad transformer library) instances typically used with IO or MonadIO but in a manner compatible with a simulation environment. For example, threadDelay in IOSim simulates the passage of time whereas in IO it blocks while time actually passes. Furthermore, the STM usage in earlier Peras prototypes was first refactored to higher-level constructs (such as STM in the network simulation layer instead of in the nodes themselves) but then finally eliminated altogether. The elimination of STM reduces the boilerplate and thread orchestration in QuickCheck tests and provides a cleaner testing interface to the node, so that interface is far less language dependent. Overall, the added complexity of STM simply was not justified by requirements for the node, since the reference node purposefully should not be highly optimized. Additionally, IOSim's event logging is primarily used to handle logging via the contra-tracer package. IOSim's MonadTime and MonadTimer classes are used for managing the simulation of the passage of time.

Node interface

The node interface has evolved towards a request-response pattern, with several auxiliary getters and setters. This will further evolve as alignment with the Agda-generated code and QuickCheck Dynamic become tighter. At this point, however, the node interface and implementation is sufficient for a fully faithful simulation of the protocol, along with the detailed observability required for quantifying and debugging its performance.

class PerasNode a where

getNodeId :: a -> NodeId

getOwner :: a -> PartyId

getStake :: a -> Coin

setStake :: a -> Coin -> a

getDownstreams :: a -> [NodeId]

getPreferredChain :: a -> Chain

getPreferredVotes :: a -> [Vote]

getPreferredCerts :: a -> [Certificate]

getPreferredBodies :: a -> [BlockBody]

handleMessage :: Monad m => a -> NodeContext m -> InEnvelope -> m (NodeResult, a)

stop :: Monad m => a -> NodeContext m -> m a

Honest versus adversarial nodes can be wrapped in the existential type SomeNode. The NodeResult captures the messages emitted by the node in response to the message (InEnvelope) that it receives, specifies the lower bound on the time of the node's next activity (wakeup), and collects metrics regarding the node's activity:

data NodeResult = NodeResult

{ wakeup :: UTCTime

, outputs :: [OutEnvelope]

, stats :: NodeStats

}

data NodeStats = NodeStats

{ preferredTip :: [(Slot, BlockHash)]

, rollbacks :: [Rollback]

, ...

}

The NodeContext includes critical environmental information such as the current time and the total stake in the system:

data NodeContext m = NodeContext

{ protocol :: Protocol

, totalStake :: Coin

, slot :: Slot

, clock :: UTCTime

, traceSelf :: TraceSelf m

}

Auxiliary data structures

An efficient Haskell simulation requires auxiliary data structures to index the blocks, votes, and certificates in the block tree, to memoize quorum checks, etc. A node can use a small state machine for each channel to an upstream node and supplement that with its own global state machine.

data ChainState = ChainState

{ tracker :: ChainTracker

, channelTrackers :: Map NodeId ChainTracker

, chainIndex :: ChainIndex

}

Each ChainTracker records node- or peer-specific states.

data ChainTracker = ChainTracker

{ preferredChain :: Chain

, preferredVoteHashes :: Set VoteHash

, preferredCertHashes :: Set CertificateHash

, missingBodies :: Set BodyHash

, latestSeen :: Maybe Certificate

, latestPreferred :: Maybe Certificate

}

An index facilitates efficient lookup and avoids recomputation of quorum information.

data ChainIndex = ChainIndex

{ headerIndex :: Map BlockHash Block

, bodyIndex :: Map BodyHash BlockBody

, voteIndex :: Map VoteHash Vote

, certIndex :: Map CertificateHash Certificate

, votesByRound :: Map RoundNumber (Set VoteHash)

, certsByRound :: Map RoundNumber (Set VoteHash)

, weightIndex :: Map BlockHash Double

}

Combined, these types allow a node to track the information it has sent or received from downstream or upstream peers, to eliminate recomputing chain weights, to avoid asking multiple peers for the same information, and to record its and its peers' preferred chains, votes, and certificates. Note that this instrumentation and optimization does not affect the simulated performance of the node because that performance is tracked via a cost model, regardless of the performance of the simulation code.

Observability

Tracing occurs via a TraceReport which records ad-hoc information or the structured statistics.

data TraceReport

= TraceValue

{ self :: NodeId

, slot :: Slot

, clock :: UTCTime

, value :: Value

}

| TraceStats

{ self :: NodeId

, slot :: Slot

, clock :: UTCTime

, statistics :: NodeStats

}

The value in the interface above can hold the result of a single "big step", recorded in a StepResult of outputs and events.

data StepResult = StepResult

{ stepTime :: UTCTime

, stepOutputs :: [OutEnvelope]

, stepEvents :: [Event]

}

data Event

= Send { ... }

| Drop { ... }

| ...

| Trace Value

The peras-iosim executable supports optional capture of the trace as a stream of JSON objects. In experiments, jq is used for ad-hoc data extraction and mongo is used for complex queries. The result is analyzed using R scripts.

Message routing

The messaging and state-transition behavior of the network of nodes can be modeled via a discrete event simulation (DES). Such simulations are often parallelized (PDES) in order to take advantage of the speed gains possible from multiple threads of execution. Otherwise, a single thread must manage routing of messages and nodes' computations: for large networks and long simulated times, the simulation's execution may become prohibitively slow. Peras simulations are well suited to conservative PDES where strong guarantees ensure that messages are always delivered at monotonically non-decreasing times to each node; the alternative is an optimistic PDES where the node and/or message queue states have to be rolled back if a message with an out-of-order timestamp is delivered. A PDES for Peras can be readily constructed if each time a node emits a message it also declares a guarantee that it will not emit another message until a specified later time. Such declarations provide sufficient information for its downstream peers to advance their clocks to the minimum timestamp guaranteed by their upstream peers: i.e., when a node sees empty incoming message queues from all of its upstream peers, it can compute a safe time to advance forward, thus avoiding race conditions or deadlock. Hence, each node can run its own thread and have upstream and downstream message queues directly connected to its peers, all without the centrally managed message routing that would form a potential bottleneck for scaling performance. The experiments described later in this document indicate that PDES is not needed at this time because simulations execute sufficiently fast without it and the cpu resources could be better used for running ensembles of simulations in parallel.

That said, it likely is the case that Peras simulations will not need to simulate contiguous weeks or months of network operation, so at this point peras-iosim uses a centrally managed time-ordered priority queue for message routing. Also, instead of each node running autonomously in its own thread, nodes are driven by the receipt of a message and respond with timestamped output messages and a "wakeup" timestamp bounding the node's next activity. If long-running simulations are later required, the node design is consistent with later upgrading the message-routing implementation to a conservative PDES and operating each node in its own thread in a fully parallelized or distributed simulation. The basic rationales against long-running simulations are (1) that ΔQ analyses are better suited for network traffic and resource studies and (2) simulation is best focused on the rare scenarios involving forking and cool-down, which occur below Cardano's Ouroboros security parameter of 2160 blocks (approximately thirty-six hours).

Sync protocol

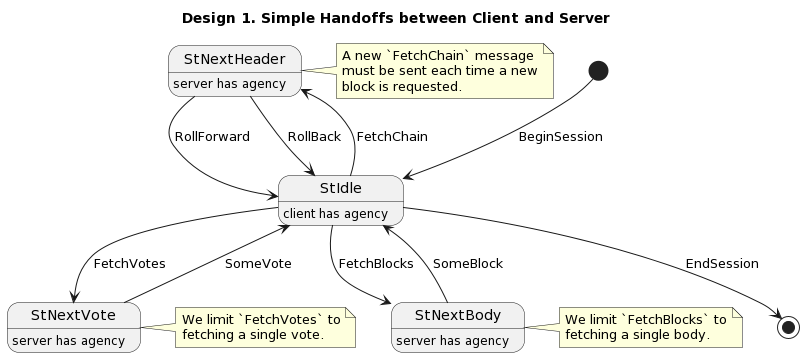

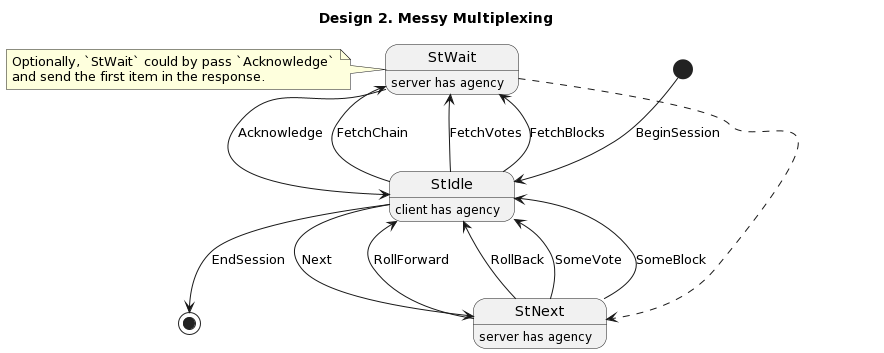

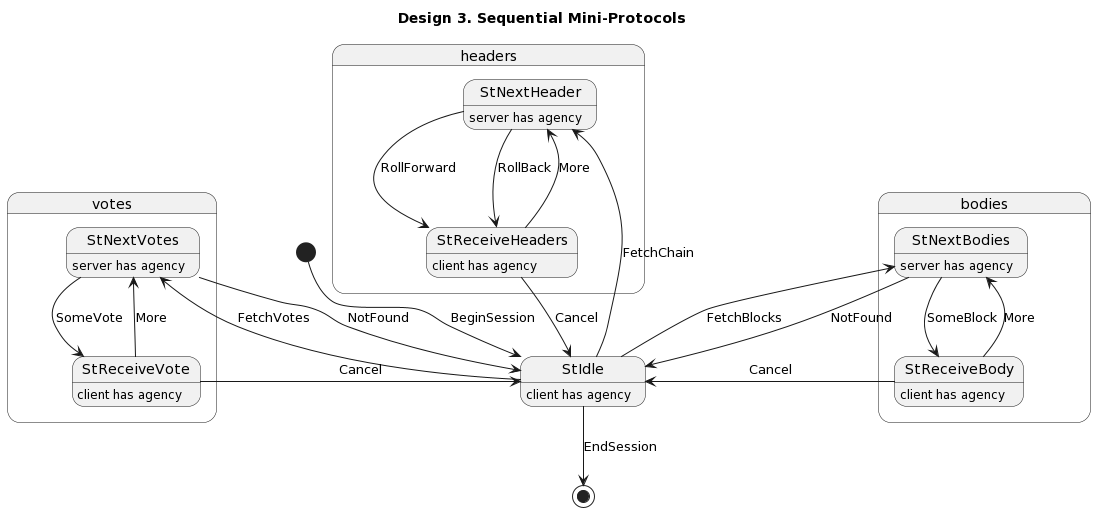

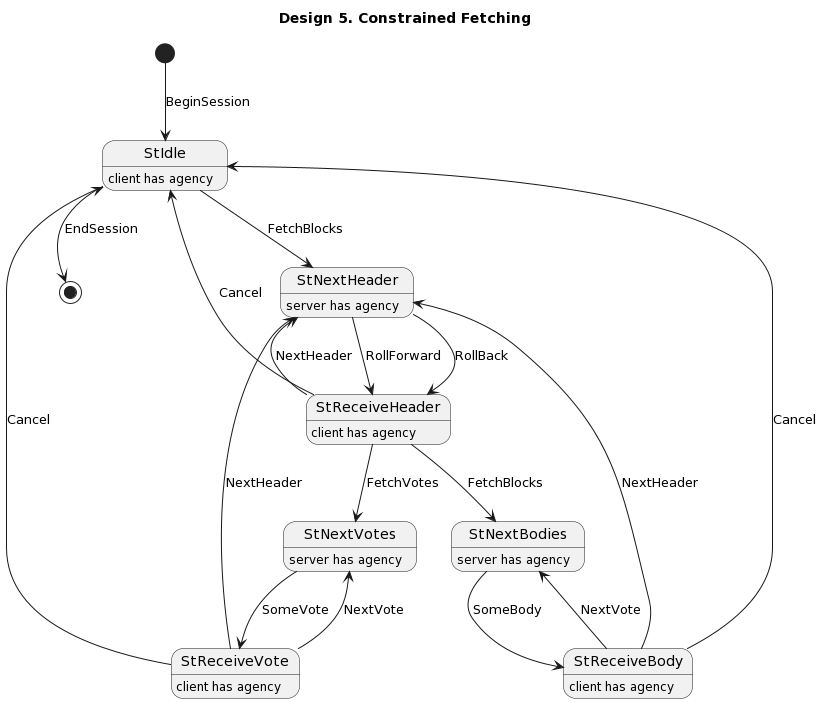

Five designs for node sync protocol were considered.

- Simple handoffs between client and server

- Closely corresponds to Agda Message

- Client could use blocking calls to tidily process messages

FetchChaindoes not stream, so anotherFetchChainrequest must be made for each subsequent block header in the new chain- Cannot handle

FetchVotesorFetchBlockswhen multiple hashes are provided, so all queries must be singletons

- Messy multiplexing

- Similar to how early prototypes used incoming and outgoing STM channels

- Incoming messages will not be in any particular order

- Client needs to correlate what they received to what they are waiting for, and why - maybe use futures or promises with closures

- Sequential mini-protocols

- Reminiscent of the Ouroboros design currently in production

- Client needs to

Canceland re-query when they want a different type of information, a pattern which differs from real nodes' simple abandonment of responses that become irrelevant

- Parallel mini-protocols

- Separate threads for each type of sync (header, vote, block)

- Client needs to orchestrate intra-thread communication

- Constrained fetching

- Supports the most common use case of fetching votes and bodies right after a new header is received

- Reduces to a request/replies protocol if the protcol's state machine is erased or implicit

| Design 1 | Design 2 | Design 3 | Design 5 |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

These highlight some key design issues:

FetchVotesandFetchBlockstrigger multiple responses, asFetchChainmay also do,- Three types of information are being queried (headers, votes, blocks) in only a semi-predictable sequence,

- The DoS attack surface somewhat depends upon when the node yields agency to its peers,

- Pull-based protocols involve more communication than push-based ones.

The current implementation uses a simple request/reply protocol that avoids complexity, but is not explicitly defined as a state machine. This is actually quite similar to the fifth design, but with no Next request. It abandons the notion of when the client or server has agency. If the client sends a new request before the stream of responses to the previous request is complete, then responses will be multiplexed.

Experiments

The simulation experiments below use slightly different versions of the ever-evolving Haskell package peras-iosim, which relies on the types generated by agda2hs, but with the now slightly outdated February version of the Peras protocol. Visualization was performed with the GraphViz tool, and statistical and data analysis was done with R.

Block production

The "block production" experiment laid the groundwork for testing simulated block-production rates using QuickCheck properties. Because the VRF determines which slots a node leads and forges a block, the production is sporadic and pseudo-random. Heretofore, the Peras simulation has used a simple probabilistic approximation to this process: a uniformly distributed random variable is selected and the node produces a block in the slot if that variable is less than the probability , where s_ns_t$ are the stake held by the node and the whole network, respectively.

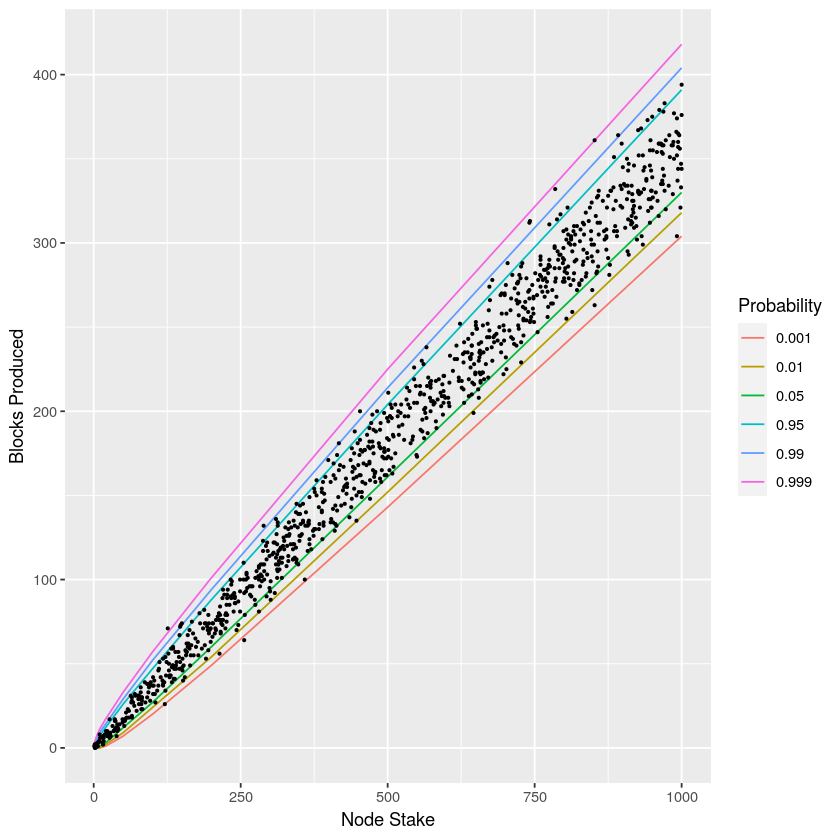

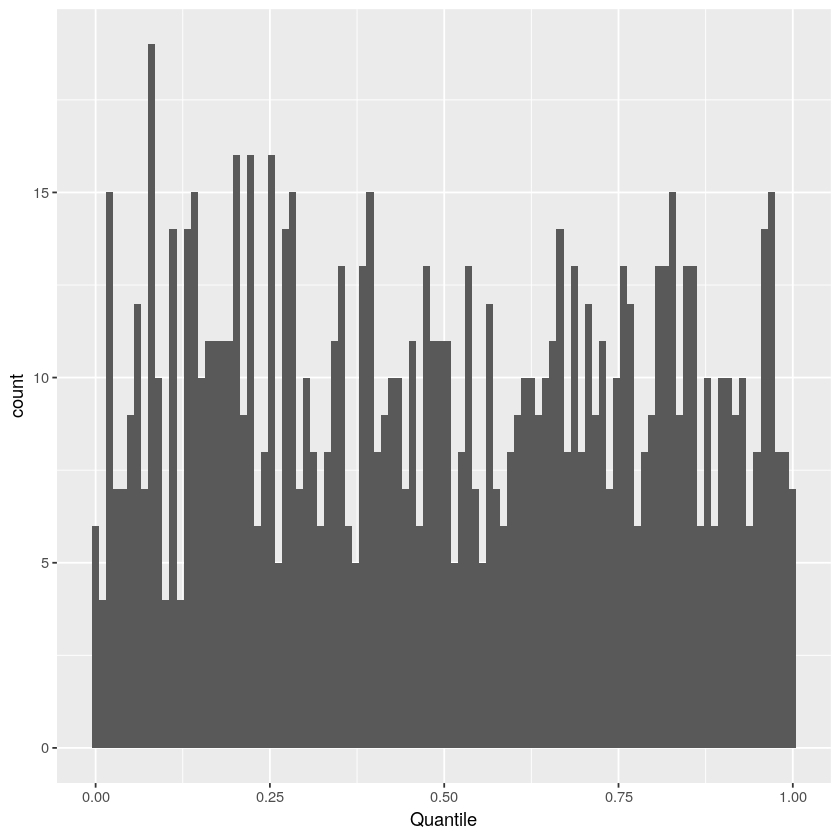

The experiment involved running 1000 simulations of two hours of block production for a node with . The stake held by the node was randomly chosen in each of the simulations. The plot below shows the number of blocks produced as a function of the node's stake. The probability contours in the plot indicate the theoretical relationship. For example, the 99.9% quantile (indicated by 0.999 in the legend) is expected to have only 1/1000 of the observations below it; similarly, 90% of the observations should lie between the 5% and 95% contours. The distribution of the number of blocks produced in the experiment appears to obey the theoretical expectations.

Although the above plot indicates qualitative agreement, it is somewhat difficult to quantify the level of agreement because stake was varied in the different simulations. The following histogram shows another view of the same data, where the effect of different stake is removed by applying the binomial cumulative probability distribution function (CDF) for to the data. Theoretically, this transformed distribution should be uniform between zero and one. Once again, the data appears to match expectations.

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test quantifies the conformance of the results to such a uniform distribution:

ks.test(results$`Quantile`, "punif", min=0, max=1)

D = 0.023265, p-value = 0.6587

alternative hypothesis: two-sided

The p-value of 66% solidly indicates that the block production count matches our expectation and the theoretical model.

Because it is slightly inconvenient to embed a KS computation within a QuickCheck property, one can instead use an approximation based on the law of large numbers. The mean number of blocks produced in this binomial process should be the number of slots times the probability of producing a block in a slot, , and the variance should be . The peras-quickcheck module contains the following function in Data.Statistics.Util:

-- | Check whether a value falls within the central portion of a binomial distribution.

equalsBinomialWithinTails ::

-- | The sample size.

Int ->

-- | The binomial probability.

Double ->

-- | The number of sigmas that define the central acceptance portion.

Double ->

-- | The actual observation.

Int ->

-- | Whether the observation falls within the central region.

Bool

The Peras continuous-integration tests are configured to require that the observed number of blocks matches the theoretical value to within three standard deviations. Practically, this means that the test measurement is a random variable that will fall outside the three σ range about once in every ten or so invocations of the CI (continuous integration) tests, since each invocation executes 100 tests.

Network and Praos chain generation

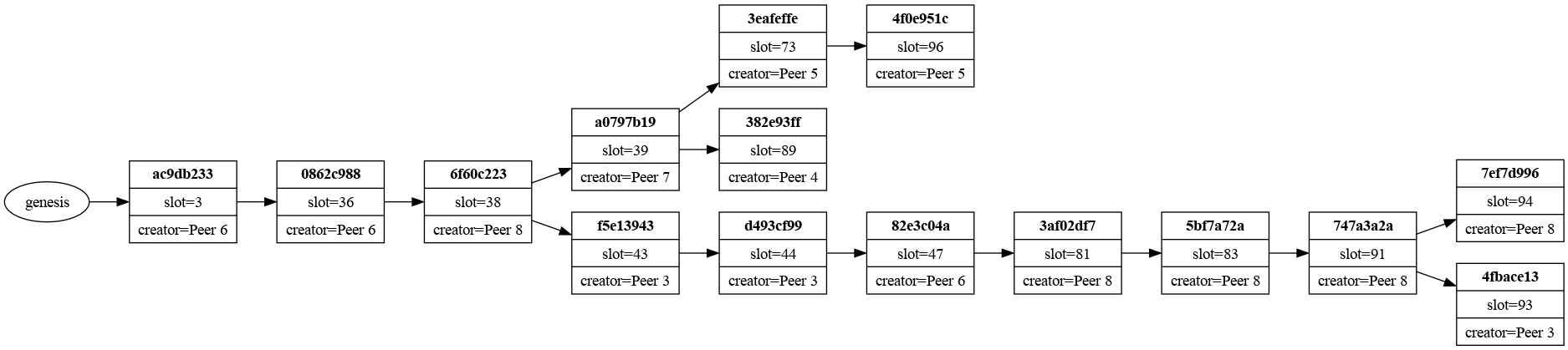

The simulation experiments generate a reasonable but random topology of peers, with a specified number of upstream and downstream nodes from each node. Slot leadership is determined according to the procedure outlined in the previous section above. Both the peras-iosim Haskell package and the peras_topology Rust package can generate these randomized topologies and store them in YAML files. The peras-iosim package generates valid Praos chains.

| Example chain | Example topology |

|---|---|

|  |

February version of Peras

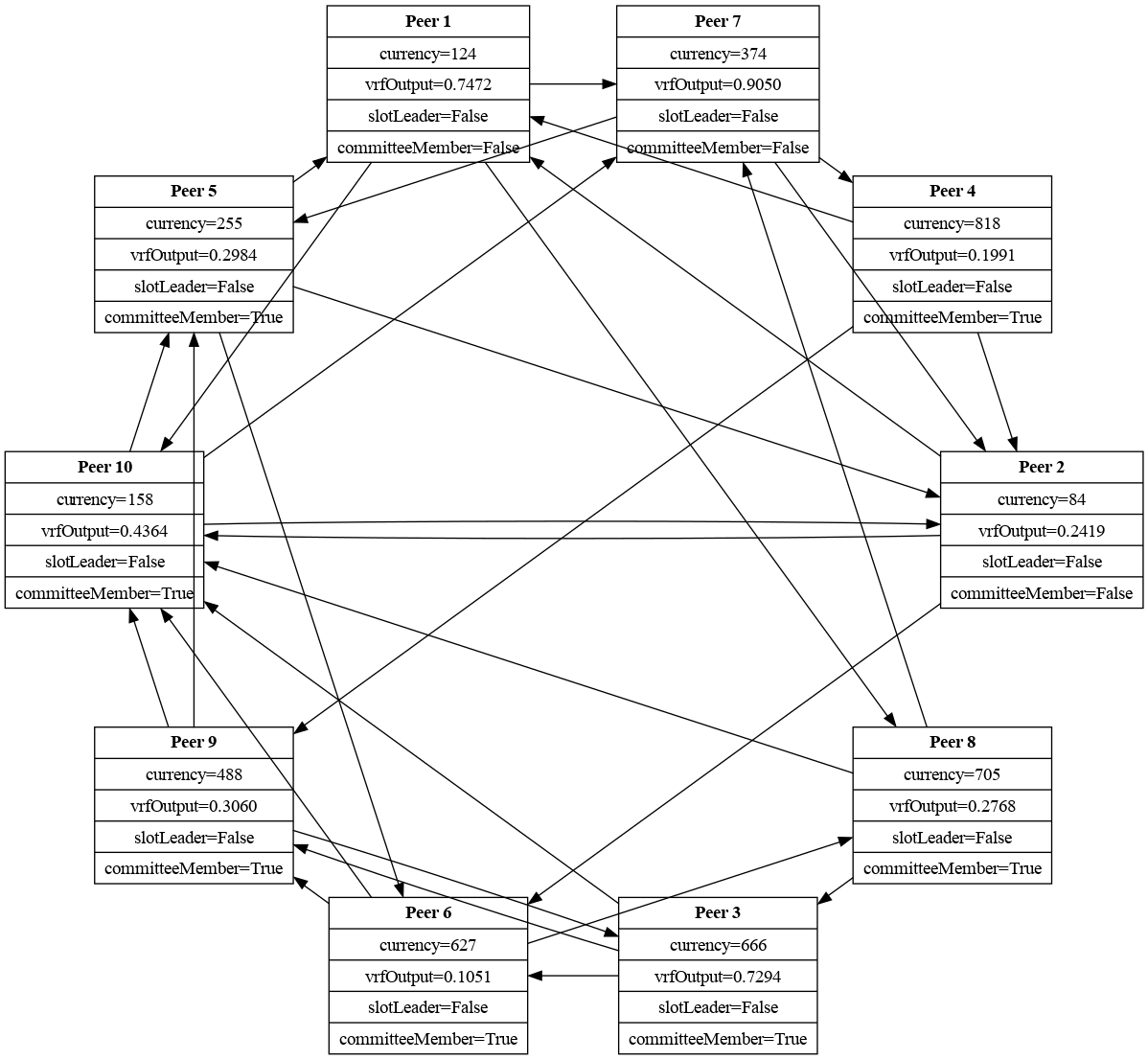

A semi-realistic set of protocol parameters and network configuration was set for a 100-node network with a mean committee size of 10. Committee selection in the following simulation was set by limiting each node to a maximum of one vote. (However, the March version of the protocol clarifies that a node may have more than one vote.) The probability of becoming a member of the voting committee in a given round is

given

where is the node's stake, is the total stake in the system, and is the mean committee size.

The following figure compares similar Praos and Peras chains, highlighting how the latter's voting boost affects the choice of preferred chain. The simulation involved 100 nodes and a mean committee size of 10 nodes; the active slot coefficient was set to 0.25 in order to provoke more frequent forking than would normally be observed. The voting boost is a modest 10% per vote.

The difference is fork adoption results from more Peras votes being received by the lower chain than by the upper one, as illustrated below.

Statistics for rollbacks, such as the ones shown below, are measured in these simulations to quantify the number of slots or blocks that are reverted: such can be used to compute the likelihood of a transaction appearing in a block that is later rolled back. The diagram below shows a proof-of-principle measurement of rollback lengths in an ensemble of simulations. The horizontal axis shows the number of slots rolled back during the course of the whole simulation, and the vertical axis shows the corresponding number of blocks rolled back: the marginal histograms show the empirically observed frequency of each. (Note that the point indicating the number of slots vs blocks rolled back do not represent single rollbacks of that many slots or blocks: instead a simulation might have had many rollbacks and the slots and blocks listed are the total among the rollbacks. Also note that the active slot coefficient was set to a high value in order to provoke more forking.) Although the voting boost weight is varied among these simulations, it has almost no effect on the rollback statistics.

Findings from the simulation runs highlight the impracticality of blindly running simulations with realistic parameters and then mining the data:

- The simulation results are strongly dependent upon the speed of diffusion of messages through the network, so a moderately high fidelity model for that is required.

- Both Peras and Praos are so stable that one would need very long simulations to observe naturally occurring forks of more than one or two blocks.

- Only in cases of very sparse connectivity or slow message diffusion are longer forks seen.

- Peras quickly stabilizes the chain at the first block or two in each round, so even longer forks typically never last beyond then.

- Hence, even for honest nodes, one needs a mechanism to inject rare events such as multi-block forks, so that the effect of Peras can be studied efficiently.

"Split brain"

This first "split-brain" experiment with peras-iosim involved running a network of 100 nodes with fivefold connectivity for 15 minutes, but where nodes are partitioned into two non-communicating sets between the 5th and 10th minute. The nodes quickly establish consensus after genesis, but split into two long-lived forks after the 5th minute; shortly after the 10th minute, one of the forks is abandoned as consensus is reestablished.

Nodes were divided into two "parities" determined by whether the hash of their name is an even or odd number. When the network is partitioned, only nodes of the same parity are allowed to communicate with each other: the Haskell module Peras.IOSIM.Experiment.splitBrain implements the experiment and is readily extensible for defining additional experiments.

Both the Praos and Peras protocols were simulated, with the following Peras parameters for creating a scenario that exhibits occasional cool-down periods and a strong influence of the voting boost.

activeSlotCoefficient: 0.10

roundDuration: 50

pCommitteeLottery: 0.00021

votingBoost: 0.25

votingWindow: [150, 1]

votingQuorum: 7

voteMaximumAge: 100

cooldownDuration: 4

prefixCutoffWeight: 10000000

The control ("normal") case is a network that does not experience partitioning:

randomSeed: 13234

peerCount: 100

downstreamCount: 5

maximumStake: 1000

messageDelay: 350000

endSlot: 1500

experiment:

tag: NoExperiment

The treatment ("split") case experiences partitioning between the 5th and 10th minutes:

randomSeed: 13234

peerCount: 100

downstreamCount: 5

maximumStake: 1000

messageDelay: 350000

endSlot: 1500

experiment:

tag: SplitBrain

experimentStart: 500

experimentFinish: 1000

In the Peras simulation, the chain that eventually became dominant forged fewer blocks during the partition period, but it was lucky to include sufficient votes for a quorum at slot 503 and that kept the chain out of the cool-down period long enough to put more votes on the chain, which increased the chain weight. It appears that that was sufficient for the chain to eventually dominate. Note that multiple small forks occurred between the time that network connectivity was restored and consensus was reestablished.

The primary measurements related to the loss and reestablishment of consensus relate to the length of the forks, measured in blocks or slots. The table shows the statistics of these forks, of which the Peras case had several.

| Protocol | Metric | Blocks | Slots |

|---|---|---|---|

| Praos | Length of discarded chain at slot 1000 | 68 | 1000 |

| Length of dominant chain at slot 1000 | 73 | 1000 | |

| Number of blocks in discarded chain after slot 1000 | 2 | ||

| Peras | Length of discarded chain at slot 1000 | 75 | 1000 |

| Length of dominant chain at slot 1000 | 66 | 1000 | |

| Number of blocks in discarded chain after slot 1000 | 3 | 137 | |

| 1 | 118 | ||

| 1 | 137 | ||

| 1 | 141 | ||

| 1 | 55 | ||

| 1 | 24 | ||

| 1 | 18 | ||

| Number of blocks afters slot 1000 to reach quorum | 18 | 304 |

The primary findings from this experiment follow.

- The complexity of the forking, voting, and cool-down in the Peras results highlights the need for capable visualization and analysis tools.

- The voting boost can impede the reestablishment of consensus after a network partition is restored.

- It would be convenient to be able to start a simulation from an existing chain, instead of from genesis.

- VRF-based randomization makes it easier to compare simulations with different parameters.

- Even though

peras-iosimruns are not particularly fast, one probably does not need to parallelize them because typical experiments involve many executions of simulations, which means we can take advantage of CPU resources simply by running those different scenarios in parallel. - The memory footprint of

peras-iosimis small (less than 100 MB) if tracing is turned off; with tracing, it is about twenty times that, but still modest.

Congestion

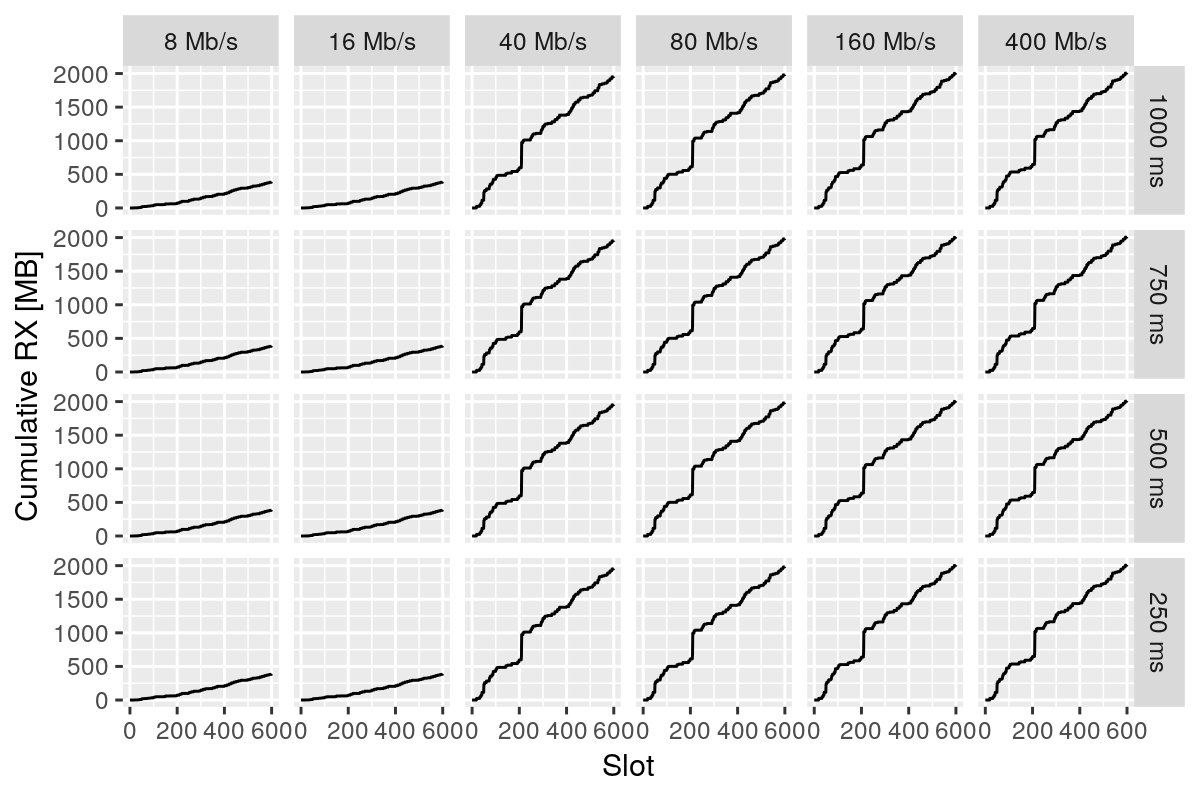

A coarse study exercised several aspects of peras-iosim in a simulation experiment involving network congestion: simulation/analysis workflow, scalability and performance, and observability. A full factorial experiment varied bandwidth and latency on a small network with semi-realistic Peras parameters. Each block has its maximum size: i.e., each block is completely full of transactions. There were 250 nodes with fivefold connectivity and a mean of 25 committee members; latency varied from 0.25 s to 1.00 s, and bandwidth varied from 8 Mb/s to 400 Mb/s, but other parameters remained constant.

The main caveat is that the memory pool and other non-block/non-vote messages were not modeled. Several findings were garnered from this experiment:

- A threshold is readily detectable at a bandwidth of ~20 Mb/s.

- It is important to realize that this simulation was neither calibrated to realistic conditions nor validated.

- Much better empirical data inputs for on node processing times (e.g., signature verification, block assembly, etc.) are needed.

- Non-block and not-vote messages such as those related to the memory pool must be accounted for in congestion.

- The existing

peras-iosimevent logging and statistics system easily supports analyses such as these.

The following diagram shows the cumulative bytes received by nodes as a function of network latency and bandwidth, illustrating the threshold below which bandwidth is saturated by the protocol and block/vote diffusion.

Rust-based simulation

The Rust types for Peras nodes and networks mimic the Haskell ones and the messages conform to the Agda-generated types. The Rust implementation demonstrates the feasibility of using language-independent serialization and a foreign-function interface (FFI) for Haskell-based QuickCheck testing of Peras implementations. In particular, the Rust package serde has sufficiently configurable serialization so that it interoperates with the default Haskell serializations provided by Data.Aeson. (The new agda2rust tool has not yet reached a stable release, but it may eventually open possibilities for generating Rust code from the Agda types and specification.) A Rust static library can be linked into Haskell code via Cabal configuration.

The Rust node generates Praos blocks according to the slot-leadership recipe. The Rust network uses the Innovation Team's new network simulation ce-netsim for transportation block-production and preferred-chain messages among the nodes.

The key findings from Rust experiments follow.

- It is eminently practical to interface non-Haskell code to QuickCheck Dynamic via language-independent serialization and a foreign-function interface.